In 1948, Jim introduced Sybil to jazz. She writes, “suddenly jazz entered my consciousness, not just the rhythm, but fascinating variations, a kind of drive and power that took over the whole instrument or group of instruments, and underneath there was this ‘beat.’ So I started to listen.” She created a number of dances to jazz, most notably A Salute to Old Friends, a tribute to Doris Humphrey, Walter Terry, Agnes de Mille, and John Martin, which was filmed but never performed publicly.

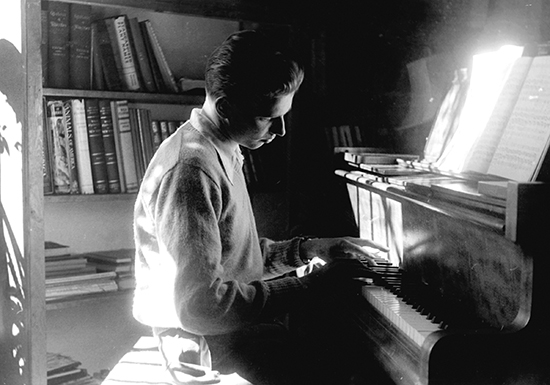

Jim also introduced Sybil to electronic music. Public awareness of this music was first raised by the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, where Edgard Varèse’s Poéme électronique was heard by two million visitors, bringing music and invention together. Jim gave Sybil tape recordings from the Fair, “and it really sparked my creativity.”

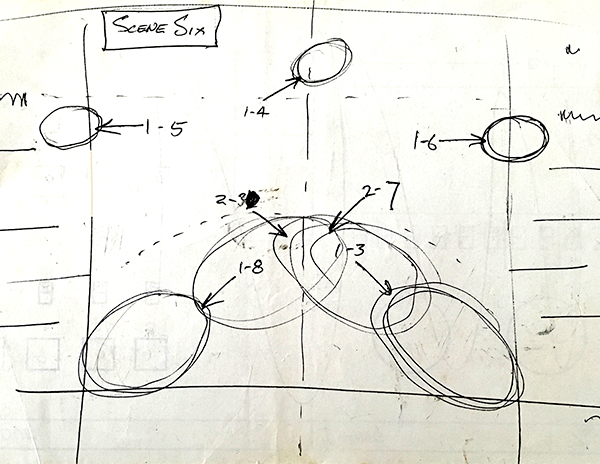

In her 1960’s concert, Fables and Proverbs, she began using avant-garde music by electronic composers. She used Jim Cunningham’s composition for Time Longs for Eternity, considered her finest company dance, and music by Dutch composer Henk Badings for the company dance, The Reflection in the Puddle Is Mine. For her solos she chose Bruno Maderno for Without Wings the Way Is Steep and Vladimir Ussachevsky for In the Shell Is the Sound of the Sea, a dance performed only once but never forgotten.

In 1969 Sybil took another leap by using music from the world’s first progressive rock band (Iron Butterfly’s 1968 hit, In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida) for her company piece, Judgement Seeks Its Own Level.

In 1991, some twenty years after the Sybil Shearer Company ended, Sybil asked Jim to become the trustee of her Trust and to join with seven others as a founding member of the Morrison-Shearer Foundation. Jim served as treasurer and remained a strong guiding hand, stewarding the legacy of his great friend even after her death in 2005. On June 29, 2014, James Cunningham passed away at the age of 92.