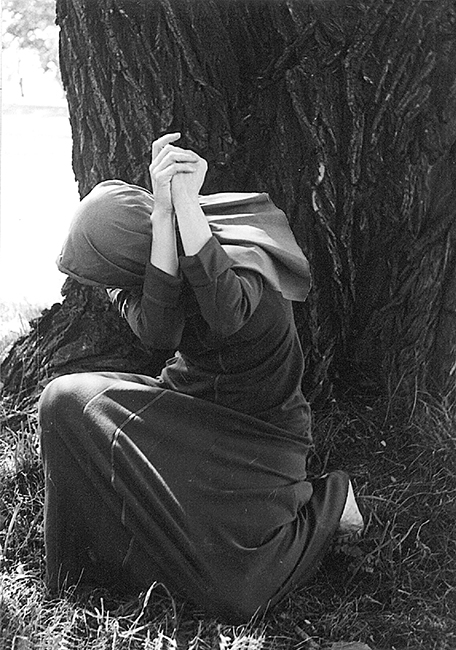

Soloist

In 1934 at Bennington, Sybil discovered the difference between being a dancer and being a creative dancer, comparable to a musical composer. In July she wrote to herself, “Everyone has told me that I have something the other dancers around me have not, and I imagined it could only be creative talent.” By August, she wrote to a friend, “I have developed a profound respect for the modern movement in every art” and by August she had “made up one dance called Anxiety.”

That fall she moved to New York City, eager to follow John Martin’s advice that “all dancers see as many art exhibitions as possible and hear as many concerts.” She began studying acting with MARIA OUSPENSKAYA but also joined Doris Humphrey’s dance class at the Academy of Allied Arts. In November 1935 she was chosen for Doris’s demonstration group, and by January was a member of the Company, dancing and touring with HUMPHREY-WEIDMAN for the next several years. In 1935, after seeing AGNES DE MILLE perform, Sybil wrote her a letter and received this reply from de Mille: “Thank you so much for your extraordinarily intelligent criticism,” and soon after, an invitation to lunch. Theirs was to become a lifelong friendship. Sybil also belonged to a small experimental group, Theatre Dance Company, started in 1936 with George Bockman and John Martin’s wife, Louise.