Shearer

FEBRUARY 23, 1912 – NOVEMBER 17, 2005

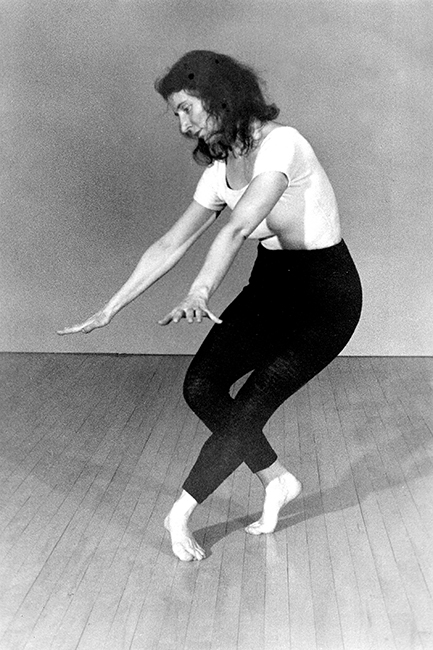

Modern dance pioneer Sybil Shearer has been deemed an original, provocative, a maverick, a priestess, nature mystic, gentle rebel, and near legendary figure. She has been called “one of the world’s foremost modern dancers” by New York dance critic WALTER TERRY (1) and “indisputably one of the greatest dancers of all time” by surrealist FRANKLIN ROSEMONT. (2) JOHN MARTIN wrote of her, “Technically she is miraculous; her body does things that are incredible, not only in conception but in execution”(3) and Walter Terry noted that “Her technical skill, creative independence, and unpredictable innovations have made her what is known as a ‘dancer’s dancer.” (4)

Sybil’s beginnings included Skidmore College, Bennington Summer School of Dance, and dancing with HUMPHREY-WEIDMAN and AGNES DE MILLE. Then, on October 22, 1941 she burst on the scene at Carnegie Chamber Music Hall, setting a radical new direction in modern dance with a solo debut. Critic John Martin gave it strong reviews and named her the year’s most promising solo choreographer.

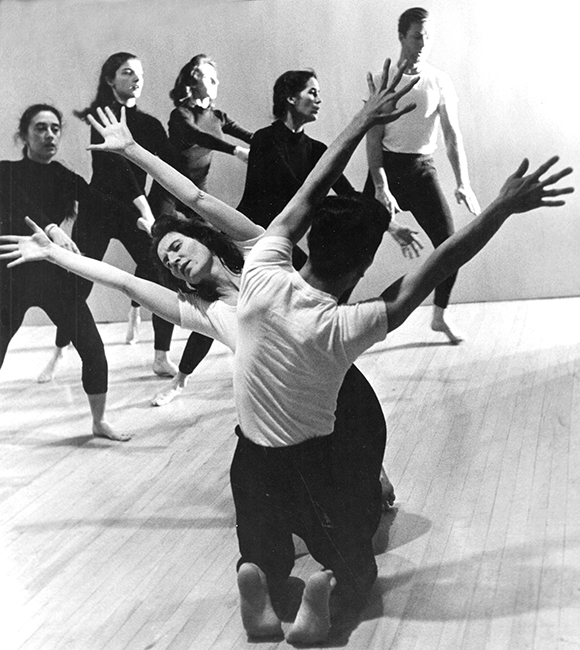

Having found her own way of working, she came to believe that New York was no place for her to develop dance as an art, and in 1942 she moved to Chicago and the soon-to-become Roosevelt College. There she was given the freedom to work independently, close to nature, and in her own unorthodox way. Within a month of her arrival, she met Helen Balfour Morrison, the photographer who would become her artistic collaborator for the next forty years.